The idea takes form

The news media has always made efforts to be accountable to the public it serves.

As far back as the 19th century, editorial standards covering accuracy, impartiality and respectful behaviour began to be codified and made public. Letters to the editor were sought and published, and occasionally they provided an opportunity for readers to take issue with aspects of the work done by journalists.

In the early 20th century, as the excesses of the “yellow press“ began to cause genuine concern, further steps were taken. In 1913, the New York World newspaper established a “Bureau of Accuracy and Fair Play” to record complaints from dissatisfied readers, and in 1916 the Swedish Government formed the “Press Fair Practices Commission” to serve as an intermediary between the public and the press.

In 1922, The Asahi Shimbun newspaper in Japan established a panel to receive reader’s comments and deal with alleged errors, and in 1938 the Yomiuri Shimbun also established an ombudsman’s committee.

Things remained that way for some time, interrupted by a war that consumed most of the developed world. But in the 1960’s the issue of newspaper ombudsmen was being put back on the agenda once more, thanks to a couple of influential news articles.

In March 1967, legendary newspaper editor and media critic Ben Bagdikian wrote that “some brave owners someday will provide for a community ombudsman on his paper’s board, maybe a non-voting one, to be present, to speak, to provide a symbol and, with luck, exert public interest in the ultimate fate of the American newspaper”.

A couple of months later, the assistant editorial page editor at the New York Times, A.H. Raskin, wrote even more pointedly that “there is a need in every paper for a Department of Internal Criticism to put all its standards under re-examination and to serve as a public protector in its day to day operations.”

The idea began to take hold. In June 1967, the first ombudsman of the modern era at a US newspaper was appointed – John Herchenroeder, at the Louisville Courier-Journal and Times.

John’s background prior to taking up the position, and his work practices in the role, helped define the template that many ombudsmen have since followed. First of all, he was a senior and highly experienced journalist, having covered a host of major stories from the Great Depression onwards, and having served 20 years as his paper’s city editor.

Secondly, he took on a prodigious workload in engaging with readers and dealing openly and thoughtfully with their concerns. He handled around 3,000 calls and letters each year, and instituted daily corrections columns for both of the newspapers he was responsible for.

Over the following twenty years, the number of ombudsmen at newspapers across the United States slowly grew to a peak of around 35. Sadly, those US numbers have since declined sharply, principally as a result of financial pressures. However, the number of ombudsmen around the rest of the world has grown during that time, and by 2020 the majority of ONO’s membership (of around 50) came from outside the US and from all corners of the globe.

We need an organisation

As the number of ombudsmen began to grow, it was inevitable that they would start to talk together, share experiences, and form a group.

When it finally came. however, the chief impetus to start an organization came not from the US, but from over the border in Canada.

John Brown, who was the ombudsman at the Edmonton Journal, wrote a series of letters to his fellow ombudsmen in the late 1970’s suggesting that an organization be established to share ideas and support each other.

The idea quickly took hold, and ONO was formed in 1980. The initials “ONO” originally stood for the “Organization of Newspaper Ombudsmen”, with the name changing to the “Organization of News Ombudsmen” a few years later when the first ombudsmen from broadcast news began to join. But the acronym was also chosen quite deliberately for another reason. It was said at the time that “Oh No!” was the most common thing an ombudsman would hear from nervous or annoyed reporters whenever the ombudsman was seen on the newsroom floor, as their appearance often heralded a difficult discussion about poor decisions or outright mistakes. So the chance to call the organization itself “Oh No!” was simply too good to pass up.

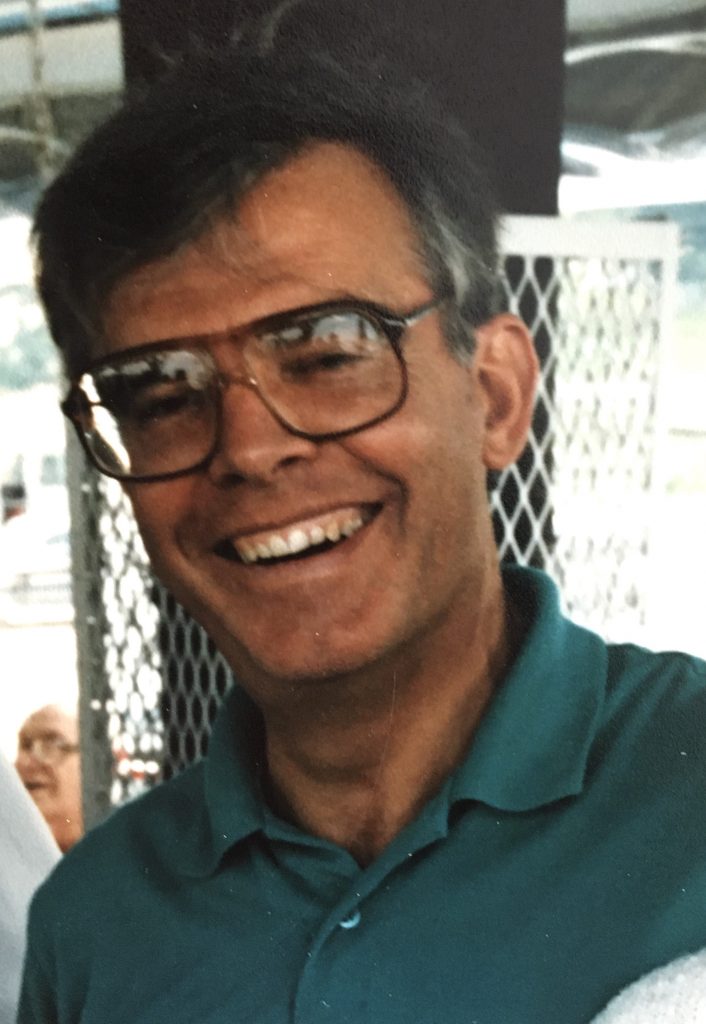

The first President of ONO was Al JaCoby. Al was a former city and Sunday editor of the San Diego Union who had moved into the ombudsman role for the newspaper.

You can read more about Al JaCoby in this fine tribute written about him by former ONO President and Executive Secretary Gina Lubrano, but suffice to say he was a gruff, no-nonsense character in the fine tradition of newspapermen between the wars.

More than one memorial noted his reputation as a curmudgeon with a heart of gold, and as an ombudsman he was a role model for many who followed.

Al not only held the President’s role for a still unbeaten five year period, he also organised and hosted ONO’s first conference, in San Diego. in 1981.

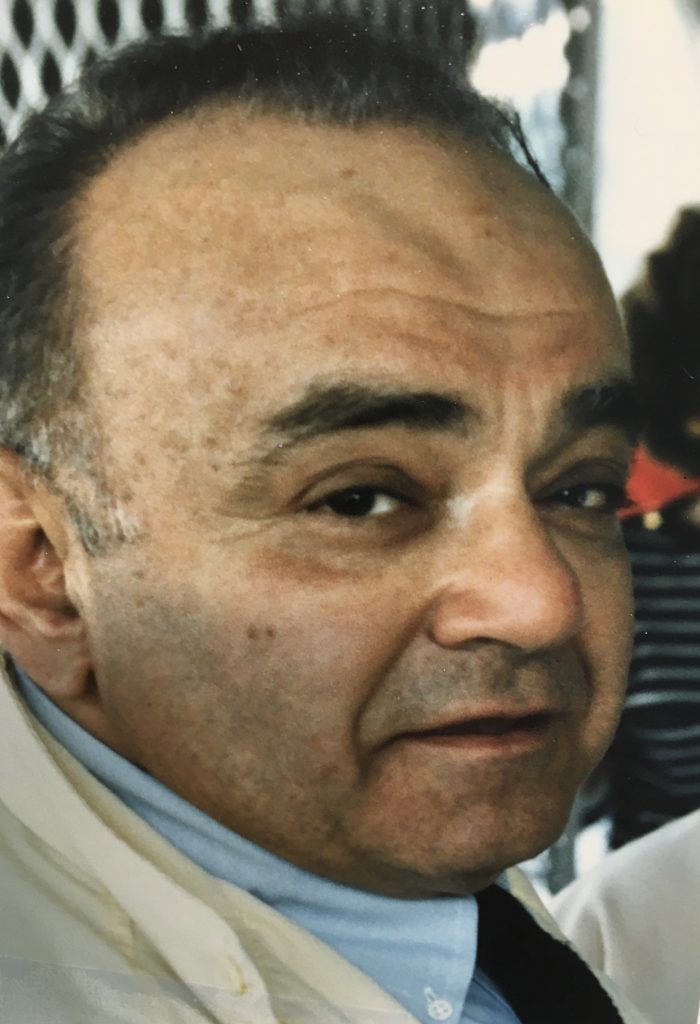

Just as important in those early years, if not more so, was Arthur Nauman, the ombudsman for the Sacramento Bee newspaper.

Arthur helped manage the day to day affairs of ONO for an astonishing 16 years, guiding the organization from its earliest days as an informal group of colleagues through to its official registration in 1996 as a non-profit organization registered in the US State of California.

In 1989, Arthur Nauman was part of a panel discussion in Washington entitled “Journalism Ethics: Some Remedies, Modest and Otherwise“. In a pithy six minute contribution, Arthur outlined the case for news ombudsmen in a way that still rings true today.

In 2020, when a happily retired Arthur spoke to ONO Executive Director Alan Sunderland, he recalled both the importance and some of the pitfalls of the ombudsman’s role. He claimed to have been given the job at least partly because the editor walked past his desk one day and noted how skilled he was at talking to angry readers. That skill landed him the job for 17 years.

Having taken on the role, he remembered how quickly invitations to staff parties dried up, and he also recalled the vital role ONO played in bringing ombudsmen together, since if they were doing their jobs properly they were ‘probably pretty lonely people’.

“Ombuddies”

From its earliest days, one of the main reasons for the organization was to allow ombudsmen to meet together, share ideas and experiences, and learn from each other.

Members began referring to each other as “ombuddies”, a nickname that has sadly disappeared over the years, but one which captures the sense of friendship and camaraderie that defined the organization. Since ombudsmen would regularly refer to themselves as having “the loneliest job in the newsroom”, any opportunity to hear from those with similar expeiences was welcome.

Right from the start, the definition of who constituted “an ombudsman” was a broad one. It was recognised that there were many different models for the role, as well as many different names.

More recently, the name of the organization has changed to “Organization of News Ombudsmen and Standards Editors” to acknowledge that wide memberhsip, but the guiding principles remain the same and so too does the acronym.

“Oh No” is too good a nickname to relinquish.

Expanding around the world

A free, independent and accountable media is an essential part of democracies around the world, and ONO has always been committed to encouraging transparent accountability everywhere it can.

A notable part of the organization’s history has been its gradual expansion into new areas and its support for ethical journalism everywhere.

After establishing itself in the US, the UK and Europe, ONO looked further afield and grew its membership in Africa, India and South America.

An important way of demonstrating ONO’s commitment to this principle was through its annual conferences. From 2000 onwards, and with the assistance of local members, ONO held its conferences in Brazil, South Africa, Argentia and India, hearing from local experts on the key issues confronting journalism in those nations.

The ideas behind ONO

Through all the changes affecting journalism in the decades since ONO’s founding, one thing has remained the same. ONO has been committed to maintaining standards in the news industry, to transparency about those standards and to public accountability.

A fundamental part of that role has always been a form of internal audit – to evaluate complaints from readers, listeners and viewers and at the same time, to explain how journalism works. As the legendary journalist and ombudsman Mike Getler at PBS once put it, the role is to ‘criticize our company when criticism is fair, and defend it when criticism is unfair”.

In a pamphlet produced in the mid-1980s, the purposes of the organization were set out.

They were:

- to establish and refine standards for the job of news ombudsman pr reader representative on newspapers and in other news media;

- to aid in the wider establishment of the position of news ombudsmen on newspapers and elsewhere in the news media;

- to provide a forum for the interchange of experiences, information and ideas among news ombudsmen; and

- to develop contacts with publishers, editors, press councils and other professional organizations, provide speakers for special interest groups and respond to media inquiries.

By 2001, ONO had expanded its thinking and guidance and produced a more detailed handbook on being a news ombudsman.

It reaffirmed the key role of the ombudsman as “to connect the public with the media organization to ensure that the content produced is of the highest standards. And if not, why not? The readers, listeners and viewers deserve no less”.

The foreward, written by then ONO President Jacob Mollerup, says “if we believe in the importance of responsible media as an essential element in our democracies, we must make self-regulation work and make it more efficient! We must show it can work in the interest of free expression and free media!”

The handbook has been revised for ONO’s 40th anniversary and it is now available as a free e-book from the ONO website as a resource for all ombudsmen and standards editor around the world.

The leadership down the years

ONO has had 27 Presidents in the forty years since it was founded.

Our first President, Al JaCoby from the San Diego Union-Tribune, was also the longest serving, having spent five years in the role. Stephen Pritchard from the London Observer served almost as long in the post. Stephen was uniquely a glutton for punishment. Having served two years as President from 2008-2010, he came back for a second two-year term from 2012-2014.

Of our 26 presidents, 17 came from the US. There were also 3 from Canada, 2 from the United Kingdom and two from Denmark. The other two countries represented are Turkey and Estonia.

While men have dominated in the position (reflecting the gender bias across so many of the senior positions in journalism generally) ONO is proud to have had seven women serve in the role.

Interestingly, the shift in focus from the US is clear when you look at the last twenty years. Of the 12 Presidents since the year 2000, only 4 have been from the US.

The future

Forty years after it began, ONO continues to prosper as a forum for ombudsmen and standards editors to share ideas and experiences, and as a champion of media accountability.

At a time when the public needs ethical, accountable and relevant public interest journalism more than ever, it will continue to advocate for these values.

*

*

*

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING:

- The ONO Handbook by Jeffrey Dvorkin, 2020

- “News Ombudsmen in North America – assessing an experiment in social responsibility” by Neil Nemeth, 2003

- “The News Ombudsman, the news staff and media accountability – the case of the Louisville Courier-Journal” by Neil Nemeth, 1992

- “The News Ombudsman – Watchdog or Decoy” by Huub Evers, Harmen Groenhart and Jan Van Groesen, Netherlands Press Fund Studies, 2010

- “Press Councils – The Answer To Our First Amendment Dilemma” by John A. Ritter and Matthew Leibowitz, 1974

- “Anything but the Ombudsman! Why Newspapers Should Avoid In-House Watchdogs” by Matt Welch, 2003

- The Reporter’s Handbook and Vade Mecum, by E.P Davies, 1884

- “Reader’s Views Toward a Newspaper Ombudsman Program” by Barbara Hartung and Alfred JaCoby,

[CORRECTION : In an earlier version of this post, the name of Mike Getler was unfortunately mispelled as “Gettler”.]